(Originally published on December 9, 2009)

For this past weekend’s miniproject, I decided to block all light from entering my eyes. I wanted to experience the world around me with one fewer sense, even if it was just for a few days. In addition to this, I wanted to see if I can help my eyesight get better. Apparently there has been some success in curing an eye condition that I have (called amblyopia) by blinding oneself for a short period of time. In my case specifically, the connection between my left eye and my brain never fully developed because when I was little, my left eye wasn’t as good as my right, and so i ended up relying heavily on my right eye to see. Blinding yourself fully for about one week, the theory goes, may “reboot” your brain and allow the weak neural connection to re-form. I may be able to see small and temporary improvement after just one weekend.

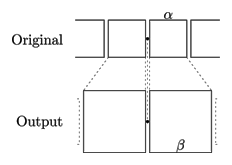

I went to sleep on Friday night wearing a special mask I made that doesn’t let any light through. I would wake up already not being able to see, which should be a good start of this experiment.

The first couple of hours have been interesting, to say the least. Things in general take much more time to do. Moving around the house is not that difficult, but I haven’t built up a mental model of the house (because I had been relying on my sense of sight all the time) so I would sometimes end up getting lost. It takes a while to feel your way through a point of reference that you recognize; if you don’t even know what room you’re in, seemingly easy solutions like tracing the walls doesn’t help.

Eating food is easier than I thought: I was able to microwave food (after solving a mini-challenge of figuring out where the respective buttons were, since they are contactless), make a sandwich, eat cereal and fruit and drink water.

Listening to TV was intriguing. I had to imagine what was going on simply based on what I was hearing. While most times it was doable, it was actually not effortless, comparable to reading a book. I enjoyed this different way of “watching” TV, but I just couldn’t do it for extended periods of time. It’s curious that losing a sense is a very efficient way of limiting–but not eradicating–one’s TV intake.

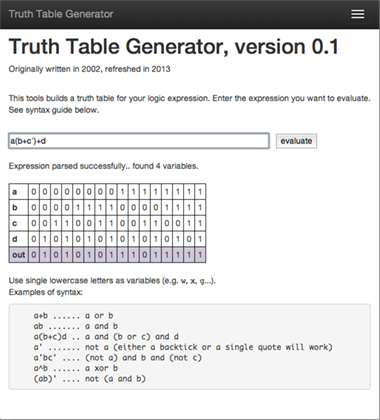

I thought I would have problems with typing because while I usually don’t look at the keyboard, I calibrate myself occasionally (and subconsciously) by glancing at where my hands are. I was worried that I would be off by one key often. Fortunately, thanks to the excellent accessibility feature of OS X and a mental model of the keyboard that I quickly established, helped me type as efficiently as when I was able to see. Keeping my palms on the laptop in a fixed location helped immensely.

Overall, I am very impressed by the accessibility feature in OS X. I’ve been able to use my computer for listening to music, reading and composing email, and writing. Apple has done a great job making the computer usable for the blind.

While it’s commonly thought that shutting off one sense makes the others more acute, at least in my case it was somewhat more complicated. I would say that I was able to perceive much more than before if I focused on a particular sense. For example, I would perceive sounds pretty much the same way as before blinding myself, but if I focused on a particular song or, say, noise in the kitchen, I was able to extract much more information from it. I could explore food with much more detail and expression than before; for example, I was able to tell the individual herbs that went into the chicken breading. I think an overall improvement of other senses is probably something that takes some time as your brain learns that it can no longer rely on the sense of sight; in the short term, the improvement of other senses during a focused effort is probably due to decreased information “noise” coming from the eyes.

Being blind also completely reshuffles what is easy and what is hard to do on a daily basis. I can receive phone calls but not make them; I don’t know what T-shirt I’m wearing. I am forced to process information much more slowly which means I can’t, for example, go through many blog posts but I’m enjoying listening to this audiobook because I can more easily create a visual representation of what is happening (the book was the Picture of Dorian Gray). Normally listening to audiobooks is somewhat painful to me — now I believe that it’s due to the “visual noise” effect.

This kind of visual sensory deprivation causes me to form certain images in my imagination, as if I was seeing them. They are usually just patterns that slowly transform into other patterns. I can’t see color yet (with the exception of a tiny blue speck of light I just saw surrounded by nothingness). This experience is uncannily like being in a dream (I also have difficulties distinguishing colors in my dreams).

I have no perception of time (ironically, I caught myself actually wearing a watch all day) or any sense of how dark it is. Even though my friend told me what time it was, I hadn’t internalized that the sun had already set. I had this strange feeling that it’s early afternoon most of the day. Overall, I’d say that time moves much faster than normally.

After the first few hours have passed I moved on from being in awe to wanting to be effective. I quickly began to look for objects around me that helped me quickly orient myself. For example, I used the carpet in my room as a reference area — I know, for example that as I follow the carpet along its perimeter I will be moving around the room and at any instant I will have a good mental image of what’s around me.

I find edges much more important than shapes; edges are something that i can trail; shapes lose their intricacies when all you have is two hands moving in three dimensions somewhat coarsely. Connections between objects and their function become much more important than their form.

Day two.

My morning routine took significantly less time than yesterday. This time I’ve been using my other senses more to orient myself in the space. For example, I’d listen to the ceiling fan and based on my perception of where I was relative to it, I was able to move around the room faster. I think I’m also slowly memorizing some distances, for example the distance in steps between my bed and the bathroom. I’m not doing it consciously but obviously in the absence of visual stimuli I have to find accurate and reliable substitutes.

My dreams were richer, fuller, but I haven’t noticed any difference between how I used to dream before the experiment and now. Writing is tougher: perhaps it’s because I’m a visual thinker and not seeing the body of the text I’ve just written makes it difficult to create structure. Writing when blind, even with my computer speaking every word as I type it, is more like on-the-fly storytelling than story construction. The only difference is that I can take my time — as a result the prose is more expressive, flows more naturally, is easier to listen, but has holes in structure.

I’ve worked out some tricks to help me get through the day. When pouring liquids, I put my finger in the container so I can feel the level of liquid and not let it overflow. Similarly, I’d check with my finger whether I put enough toothpaste on the toothbrush. I pour the shampoo slowly on my hand and try to figure out how much of it I poured based on the cold feeling that shampoo has on the palm of my hand.

I think I fidget much more now, again probably due to sensory deprivation.

The most challenging, but also the most remarkable difference is in how I process information. Without the sense of sight, all processing is linear: I have immediate access to the last few words, or bars (if writing music), and the rest has to be filled by my brain. Instead of focusing on structure, I need to think about flow — one thought transforming into another; one world blending into another. I produce much less, but what I produce is richer because it has to stand on its own, be engaging at all times. It’s stateless.

Making music was a great experience — in fact, I think I will continue to experiment with music when blind. I’d find myself not to cling to the same keys as I always do. Recording music is tricky but other than that I felt much more creative. Perhaps, if you don’t see the white and black keys, you start focusing on what’s behind them rather than on them.

Naturally, I am more aware of what is where now. While previously my brain could be lazy (it didn’t have to compose elaborate models of the room and objects within it, because all it took to know was a quick glance), now the cost of gathering information is relatively high: I have to look around and feel my way around so I remember much more. I know where all the articles of clothing are in my room. I know what’s on the night stand, in order from left to right. I remember where I put things.

Going about my life was fairly easy when everything around me was in my control. But when things changed and I wasn’t aware of them, I found it fairly difficult to adjust. For example when some dishes were rearranged, it took me a long while to re-adjust. After I’d noticed the world is different from my model of it, I would have to rebuild my model.

I found it pretty easy to interact with other people. In fact, the lack of visual “noise” meant that I could engage much more in what the other person was saying. I remember these conversations better now.

I took my blinds off on Monday morning. There was no “epiphany”; I also wasn’t bothered by light. Curiously, my right eye (the good one) exhibited similar problems as my left one has always had. This was temporary, but I think it means that the “reboot” theory might actually work — the brain weakened the connection to my right eye. It hadn’t been weakened enough to eliminate the bias, but it was a good start.

While the moment immediately following the regaining of sight wasn’t spectacular, the following thirty minutes were… surreal, to say the least. I felt a little out of it, as it the world around me had undergone some strange transformation while I was away. Perhaps that’s what (temporarily) regaining depth perception feels like (I have non because of amblyopia).

In all, I felt empowered to do some of the things I was able to do before, and was impressed to be able to get more from some others. However, I wasn’t as productive as normally. True, part of it was the fact that I’ve only been blind for two days — I am sure that people who are actually blind have perfected the routines that took me an hour to do. It’s also not at all certain whether that loss in productivity more than repaid itself in the higher quality of the work I came up with during those two days.

Editorial Note

After I published this, I received a comment from a person named Jeremy, which I wanted to include here:

As a blind person, I am a little upset by your generalizations about the blind experience. all your obstacles could have been overcome with a little bit of creative thinking and some adaptive aids. I manage quite well with a screen reader as you mentioned but my cell phone also speaks as well as my speaking/braille watch. I hope that your realizations are taken with a grain of salt, as you didn’t really get a chance to fully accept the differences and adapt over time.